How can Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways (DAPP) help mitigate disasters?

Policymakers and other stakeholders have one big problem in common when it comes to managing and mitigating risks and hazards: nobody really knows what to plan for. The Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways can support taking decisions despite these deep uncertainties by rethinking the way how we address risks and hazards.

Natural risks and hazards, like those exacerbated by climate change, imply lots of uncertainties. Extreme weather events, for example, are becoming more frequent but it is less known when, where and to what extent they will occur. The same applies to sea level rise. The uncertainties around natural risks and hazards make it difficult to account for their socio-economic consequences, like population dynamics, urbanisation or migration.

Introducing flexibility to risk management

Regardless of these uncertainties, policymakers still need to take decisions on risk management actions and long-term strategies. Livelihoods and infrastructure need to be protected against potential damages today and in the future. Additionally, the big challenges of our times, like using energy more efficiently, need to be tackled while the central questions of risk management still need to be addressed:

- What conditions do we design for and protect against?

- How do we account for future developments within our planning horizon?

- If we take an action, what limits do our actions have?

- What happens if the threshold we have our measures designed for is crossed?

Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways (DAPP), developed by Deltares and TU Delft, helps to analyse the performance of actions for a range of scenarios capturing the deeply uncertain conditions. By doing so, combinations of actions can be identified that are flexible in the short-term, but robust in the long-term. Hence, while the engineering approach of the past decades favoured robust solutions, like a sea wall, DAPP give more importance to flexible,nature-based solutions, like a mangrove forest, as they offer the flexibility to be scaled up or down as needed at a relatively low cost and ecological impact, depending on the future development of the system.

By using DAPP, we identify ‘low regret’ interventions that provide ecological and social co-benefits in the short term but can easily be adapted or complemented with additional measures in the long term if the initial measures prove to be insufficient or when a threshold is crossed. In short, DAPP accounts for decision-making over time and therefore allows for adaptive plans of short-term actions and long-term options, which can be adjusted in the future based on new knowledge or changing conditions.

Decision-making takes a central role in adaptive risk management. DAAP explicitly require authorities to take action at several moments in the process, when the implemented measures reach their thresholds or to decide what additional interventions are needed. The Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways are best used in situations where infrastructure with a long life-time is concerned, high investment costs, strong path-dependency is expected or the larger system is sensitive to uncertainties, like the Thames Estuary 2100 project, the Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100. DAPP has been applied in a wide field of decision-making processes including flood risk management, drought management, planning of coastal areas and other diverse applications.

Adaptive hazard risk management in 7 steps

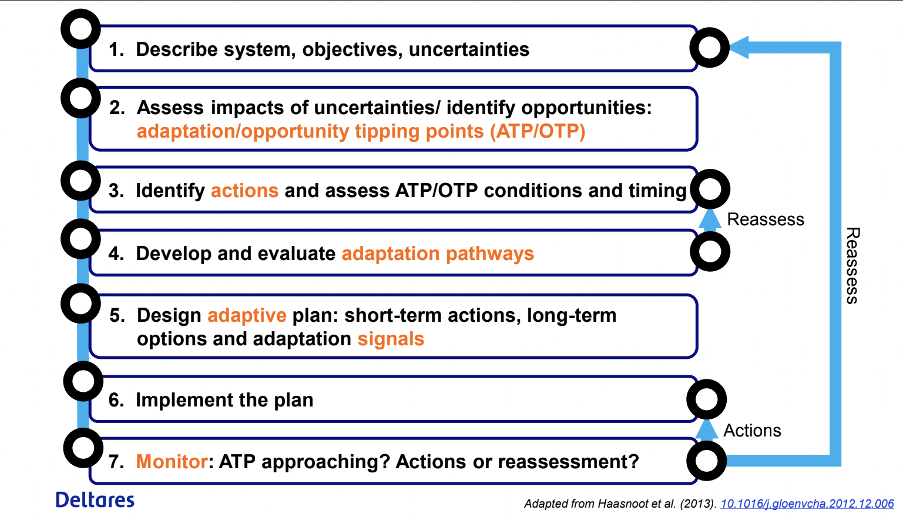

Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways are developed by following the step-by-step plan. Going back to previous steps and reassessing decisions taken earlier on is essential to making sure that the chosen measures and solutions correspond to the real-world requirements.

7-step plan to develop Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways

Step 1: Describing the system

To get started, we need to describe what we are dealing with including the system characteristics, objectives, and constraints under present and future conditions. A range of well-established approaches can be used: A common policy analysis can be carried out to map existing measures, or the DPSIR framework can be applied to identify drivers, pressures, state, impact and response in a study area. Other methods include causal loop diagrams or cause-effect analysis.

Additionally, the scenarios we are planning for need to be defined. These scenarios address the most relevant sources of uncertainty and thus cover a range of plausible future states (e.g. in terms of climate change, population growth, socio-economic transformations).

Step 2: Identifying tipping points

As a next step, we need to understand the impacts of natural hazards and potential impact thresholds that are acceptable by stakeholders (e.g. residents, water authorities, farmers) or describe limits of the system to cope with the impacts beyond which significant changes to the system would be introduced For example, what temperature rise or population increase can our system deal with before it has reached its tipping points and results in too many heat-related health incidents, or insufficient provision of services.

Step 3: Identifying and assessing actions

Step 3 uses the identified thresholds in step 2 along with the identified scenarios to find effective policy actions for adaptation or seizing opportunities and characterise their efficacy and potential timing. If no suited actions can be identified, the performance indicators identified in step 1 need to be reassessed.

For example, if we are looking for a way to keep the shipping volume for a river with low water levels above an economically feasible level, we would assess the use of ships of different sizes to identify for how long these measures can delay reaching the thresholds (shipping is not economically feasible any more) under the different scenarios.

Step 4: Developing and evaluating the pathways

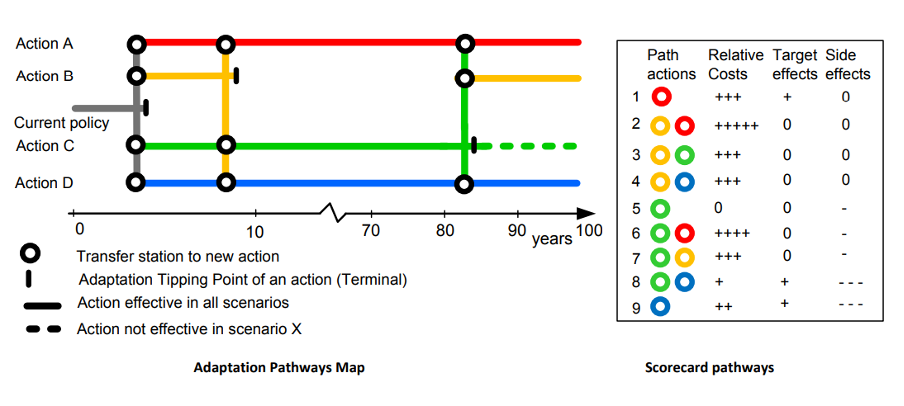

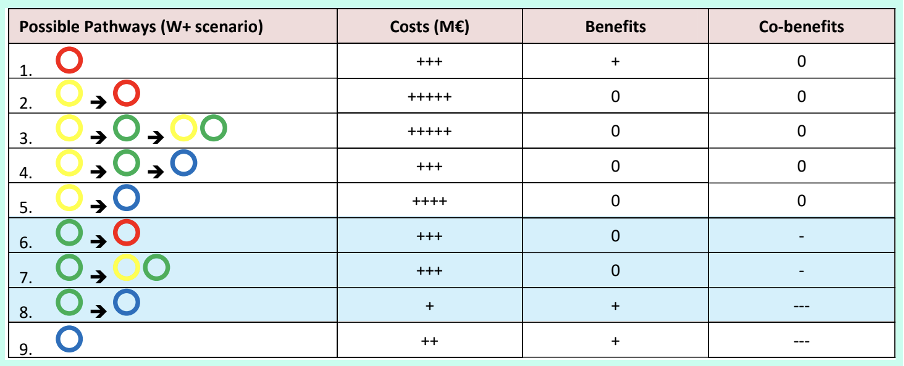

Using the set of effective policy actions from step 3, in this step adaptation pathways – meaning sequences of policy actions – are developed and evaluated based on the initially identified objectives, their plausibility and other parameters (e.g. financial costs). The result is a so called pathway map, which indicates logical sequences of policy actions, the timing of the implementation of certain actions and uses score-cards to present the results of the evaluation. A useful tool to create both outcomes is the Pathway Generator that can assist in the visualization of the pathway maps.

In general there is not one single right adaptation pathway but a set of preferable pathways. The different pathways can be assessed using for example cost-benefit analysis. Stakeholder interests, their involvement and politics can play an important role in evaluating the different pathways.

Cost-benefit analysis of using smaller or medium-sized boats and small or large dredging

Step 5: Designing the adaptive strategy

After the evaluation of the preferred pathways, an implementation strategy is developed. This includes the identification of initial actions and long-term options. In this crucial step, we have to set up a monitoring system to make sure that signals of the changing system are identified to initiate planned actions on time or to adapt the initial plan based on the observed developments. Furthermore, it is identified which authorities will be in charge of the implementation, where the financing will be coming from or who will be in charge of monitoring the changes to the system. Also, it will be assessed whether additional preparatory actions are necessary to keep preferred longer-term options open.

Step 6: Implementing the plan

This step is based on the previous one and covers the actual implementation of the chosen actions.

Step 7: Monitoring the plan

The identified adaptive strategy will result in initial actions, and then continious monitoring of the system. Further actions are suspended until the monitoring gives a signal. This could either trigger the implementation of the next policy action or initiate additional research or re-visiting the DAPP approach using the additional knowledge.

Accounting for multi-sector and multi-hazard scenarios

The existing DAPP methodology is not yet ready to be applied in multi-sector, multi-hazard contexts. Such context are very complex and interrelated, as you need to account for the dynamics and interdependences between different sectors as well as for hazard interactions. Interactions between sectors could for example increase the damages and therefore produce additional losses that need to be accounted in risk management. For example revenues losses of farmers can occur if crop yield are lost due to flooding of the field but also due to indirect impacts, in case the operating transport system is not working to distribute crops to supermarkets where it can be sold. Furthermore, multi-sector systems offer the need to evaluate the performance and trade-offs of policy actions not only with regard to one single sector, but with regards to multiple, resulting in cooperative strategies, where the interests and needs of all involved stakeholders are suffieciently represented.

Furthermore, interactions of hazards (e.g. close sequence of a wildfire and a flood, or the triggering of landslides by an earthquake) can lead to changes in the physical characteristics of the system. A wildfire could destroy a significant part of vegetation which could lead to intensified floods due to reduced storage capacities by vegetation. At the same time, an earthquake could damage buildings and the subsequent landslides fully destroy it, while a undamaged house would have withstand the impact of the landslides.

A tailored DAPP methodology will be developed to guide users through the required steps to analyse the existing system and future states while accounting for multi-hazard interactions and multi-sector interactions. It will be helpful for the pilot regions to develop forwardlooking disaster risk management pathways.

Conclusion

The Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways framework (DAPP) provides a framework for the analysis of policies and is a promising tool to implement the paradigm shift to manage uncertain risks dynamically with the long-term options in mind, in line with MYRIAD-EU’s project mission. DAPP offers a versatile approach to risk management by incorporating uncertainties into the planning process and identifying strategies that are both robust and flexible.

To identify the pathways, different tipping points and scenarios are first assessed to understand if and when limits, thresholds of acceptable performance or opportunities occur in our system. When we are exploring different adaptation options, we also need to identify ‘regrets’ and path-dependencies to be able to formulate adaptive plans. Once the short-term adaptation solutions foreseen in a pathway have been implemented, we need to monitor our system to make sure we identify approaching thresholds on time and are able to react accordingly. Engaging stakeholders throughout the process to make sure to come up with a satisfying solution for the involved actors is crucial to the success of the DAPPs.